|

|

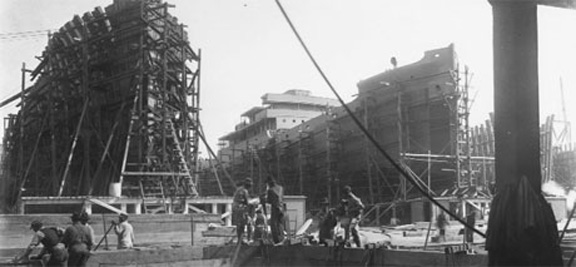

Joiners preparing a ship frame; SS Abbeville and SS Bayou Teche in background.

Photo: Courtesy of Walter F. Jahncke Collection. |

They would have been standing on the property of the Jahncke Shipyard, which encompassed much of Madisonville’s current footprint near where the baseball fields and Maritime Museum are today. The shipyard employed some 2,200 workers to construct six wooden ships in fulfillment of a contract with the U.S. Navy, an effort that constitutes the largest industrial effort in the northshore’s history. Though World War I ended before all of the ships were finished, the shipyard changed the face of Madisonville forever.

Fritz Jahncke emigrated from Hamburg, Germany, to New Orleans in 1870 at the age of 19 to work as a mason. Fritz was enterprising, eventually starting his own company and building a reputation. Jahncke Service Incorporated began paving the mud sidewalks of Uptown New Orleans, which in the late 1870s was considered revolutionary.

In another farsighted move, Fritz rented a steam-driven hydraulic suction dredge to gather sand and shells from the Tchefuncte and other area rivers for use in concrete throughout New Orleans. He was the first to use such a dredge in this way; previously, workers dug up the materials with shovels. With this advancement, Fritz dramatically increased the efficiency and speed of construction in New Orleans. He’s credited as the first person to install paved sidewalks and streets in the city.

|

|

A ceremonial landmark for production—laying a keel.

Photo: Courtesy of Walter F. Jahncke Collection. |

Madisonville was the perfect location for Fritz’s growing business. “Because of the river, it was just the spot,” says Rusty Burns, a local history enthusiast with an interest in the Jahncke Shipyard. The river gave Fritz access to the raw materials he needed, while allowing him easy access to the lake and to New Orleans.

Fritz continued expanding business on both sides of the lake, acquiring yards, warehouses, docks, storage facilities and equipment. He’s largely credited with the development of the New Basin Canal, which he used to transport raw materials from the northshore. In fact, once he started using it, Jahncke was the canal’s largest user. Later, he helped build the Port of New Orleans.

When Fritz died in 1911, he passed his company on to his sons, Ernest Lee, Paul F. and Walter F. Jahncke, and the shipyard soon had another purpose. In 1917, the U.S. Navy awarded Jahncke Service a contract to build six wooden-hull ships. Though Fritz died before the United States entered World War I, there’s some speculation that he and his son, Ernest, might have foreseen the conflict and purchased land and equipment for that purpose.

“Fritz Jahncke fought in the Franco-Prussian war for Prussia, so he was familiar with the political environment of Europe when he emigrated,” says Steve Jahncke, who worked as a salesman at Jahncke Services and is a great-grandson of Fritz. “I know he went back to Germany in 1909, and it's entirely possible that he picked up on the vibes of what was going on then. He could have been astute enough to put two and two together and to come back and sit down with his sons and say, “This is on the horizon.“

“But he was well into the acquisitions in 1909,” says Rusty. “A lot of the land was already purchased.” The family isn’t sure whether to give credit for the contract to Fritz or Ernest—or both.

|

|

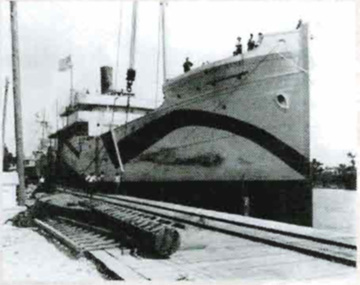

The SS Bayou Teche with pontoon lifting her stern to assure passage over the shallows

of the Tchefuncte River and the Mississippi Sound Photo: Courtesy of Walter F. Jahncke Collection |

As is often the case with family histories, Davis and Steve have varying memories of family lore. Word of mouth has changed the stories slightly over the generations, and many details have died along with the people who knew them. Perhaps the best documentation of the shipyard during the war is the hundreds of photographs made from glass plate negatives collected by the family.

The photographs show construction of five cargo steamships, each of which was 300 feet long and would have weighed around 3,000 tons upon completion. The building effort must have been frenzied. The workers constructed the ships and the ways to launch them simultaneously because time was short. There were no housing facilities in the area, so Jahncke Service also had to construct boarding houses for the workers.

“It was such a major effort to capitalize that whole yard, to do what they did. They had to capitalize this whole town, this whole region,” Rusty says. “The building of sawmills—and think of all the transportation needed, vessels and tugboats and pushboats and on and on and on. And housing. There was a real shortage of housing in Madisonville [at that time]. It had to be a tremendous effort.”

|

|

The completed SS Bayou Teche

Photo: Courtesy of Walter F. Jahncke Collection |

The SS Bayou Teche was launched in March 1918, and the SS Balabac on Sept. 29, 1918. The finished boats were floated on large pontoons to ferry them across the shallow areas at the mouth of the Tchefuncte, across Lake Pontchartrain and through the Rigolets to the Mississippi Sound.

The war’s hostilities ended Nov. 11, 1918, less than two years after the United States entered. The Jahncke Shipyard had completed and delivered only two of the six ships in the contract. The exact history of the ships during the war is unclear. On June 28, 1919, the United States and its allies signed the Treaty of Versailles with Germany, formally ending the state of war.

Two other ships were completed, except for minor details, and were launched later, the SS Abbeville on Jan. 19, 1919, and the SS Pontchartrain on April 6, 1919. Photographs show a fifth, unnamed ship under construction at the same time as the others, though it was never completed. Rusty says it was ferried to the east side of the river and burned, and its hull is still visible today when the water is low. The skeletal remains of the massive ship stick out of the water just south of Marina del Ray.

|

|

Launching of SS Pontchartrain, April 6, 1919.

Photo: Courtesy of Walter F. Jahncke Collection |

“Jahncke had a significant volume of work during World War I,” says Sally Reeves, a New Orleans historian currently undertaking a survey of Madisonville’s historic homes and buildings. “When the war ended, many people were out of work. Before that, they were the largest employer in town. It turned out to be sort of a bubble.”

Jahncke Service continued running the shipyard and supplying concrete for construction. Throughout its history, the company supplied concrete or other building materials for many well-known structures in New Orleans, including the Elysian Fields overpass, the Canal Building, Charity Hospital, Jackson Brewery, the Falstaff Brewery and the Sears Roebuck Building. The entire company, including its various entities, eventually dissolved. “By the late 1960s, the family got to fighting among themselves and classic corporate greed took hold,” Steve says. The company was sold and the shipyard in Madisonville came under new ownership. It was finally closed around 1970.

Today, the only remnants of the shipyard are a handful of unassuming concrete foundations in the green space between Main and Pine streets, near Bordeaux Street. The foundations once held winches to hold the ships and steam engines to power the shops.

Rusty and Davis agree that the venture wasn’t very successful. “They really expected the yard to do a lot more than it did. It just didn’t prove to be as productive as they wanted it to be, and I would say the reason for that is because the war ended so quickly,” Rusty says.

“For what it took to build the entire infrastructure, it could have gone on for 20 or more boats,” Davis says. “So it couldn’t have been financially successful.”

But perhaps that wouldn’t have disappointed Fritz Jahncke, had he lived to see the effort. His company’s motto read:

| We Shall Build Good Ships Here At A Profit If We Can At A Loss if We Must But Always Good Ships |

The Jahncke Shipyard might not have made the company rich, but it had a significant impact on Madisonville. “It had marvelous influence, but on the other hand, it was short-lived,” Sally says. She points out that the presence of the shipyard meant no homes could be built in that area until it was torn down. To this day, there’s a disconnect, she says, between the north and south parts of Madisonville as divided by Highway 22. On the south side are mostly new homes that could not be built until the yard closed, whereas the north side is full of older homes.

Apart from the visible impact of the shipyard, its presence built up the town in a surge of activity that set a foundation for the future. “It was a boom of prosperity that got Madisonville out of the doldrums it had been in since the Civil War,” Sally says.

“It was so productive for the economics of St. Tammany and Madisonville,” says Rusty. “It revolutionized Madisonville.”

Without the shipyard, Madisonville might look very different today.